Neolithic Göbekli Tepe and Temple Tantrums

This is Part Two of the story from Urfa: Mustafa and a Neolithic Rant

I had emailed Professor Schmidt some weeks before and he informed me his springtime digging period was about to end and that Fridays were off for everyone. I told him I’d come on Saturday but I never heard back from him. Mustafa, our guide and hotelier, offered to guide us and drive us there for a good price, and so we took him up on it. He picked up his well rehearsed rant from the night before. (You should probably read that to understand what happens to him here.)

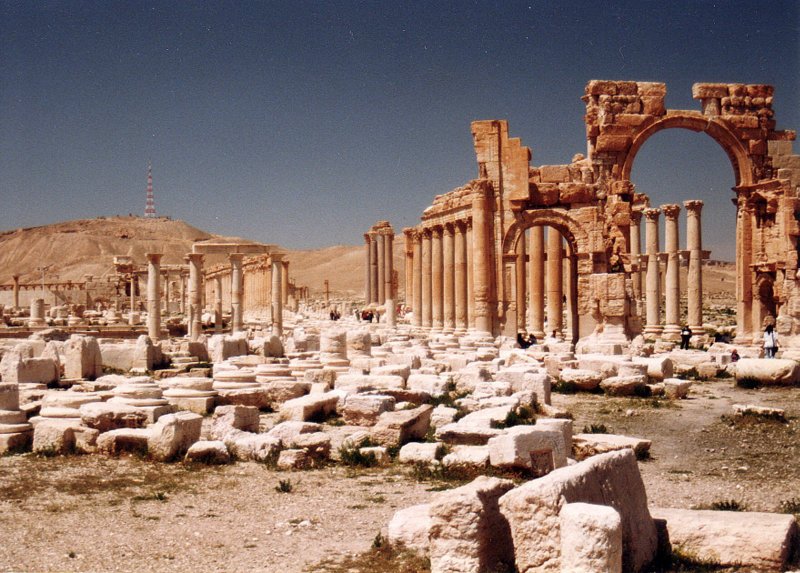

We drove up the long dusty road to a hill that stood just a bit higher than everything else. A tour bus was already there. We paid our tickets – with no small amount of grumbling from Mustafa – and followed a new wooden walkway still in the process of being laid out and smelling of creosote.

I had mentally prepared not to expect the grandeur of Stonehenge, and while wood beams and supporting cobble cluttered up the scene a bit, the concept of it all left me awestruck. Mustafa took us around the site with bits of narration, but mostly we spent a long time just absorbing the site, trying to imagine it when hunters and gatherers came here for some sort of symbolic or spiritual purpose. I took a ridiculous amount of photos, trying to work around the wooden structures that shielded the site from the elements and cast frustrating shadows. But though we dawdled and circled the top of the hill, in the end, it appeared the professor was not coming to the site that day.

We strolled back to the parking area and were just about to leave when Mustafa said he saw the professor’s car in the distance. “What should we do? Do you want to wait?” I could tell Mustafa seemed eager to leave, and often I cave out of a desire not to inconvenience anyone, but damn, I may never be back here and maybe the professor will agree to see me. One of the site guard had refused to radio or go tell him I was there, because everyone and their cousin who once read a book on history or saw this site in a documentary wanted to introduce themselves and take up the professor’s time. That included me, of course. So I handed him my card and said, Make sure the professor gets this card; I will email him to tell him to ask you for it.” The guard grimaced. While bothering Schmidt might get him in hot water, the card, if important, might do the same if it turns out he didn’t deliver it. Off he went up the hill.

Meanwhile another site guard came up to Mustafa and they had a terse back-and-forth conversation I couldn’t quite follow, and the guard spoke low and coldly. “Who?” So-and-so. “Why?” “Says who?” “What did he say?” No one smiled and they stood with noses a bit too close. Mustafa left and I looked back up the hill to my messenger who was returning and gesturing for us to head up the hill to the professor’s trailer. We were cleared to go see Dr. Schmidt!

Tip tapped my shoulder, “Hey, I think they are having a fight.” I remember an old Istanbul friend who once cast doubt on a character we had met by calling him, not kindly, Anatolian. “They have tempers,” he claimed. Throughout this trip deep into Anatolia we had seen some very uncharacteristic aggression, something I had never really witnessed much in all my years of traveling and living in Turkey. Well, so much for stereotypes, maybe there was something to it.

In fact, as it turned out, it took four men to pull one of the site guards away from Mustafa. I hadn’t realized who was involved because I, the selfish fellow I was at that moment, was off running up the hill like a schoolboy to the cafeteria ice cream party.

Schmidt wore light clothing and a hat to protect him from the harsh sun, and judging from an old photo I had seen online, the syrupy sweet delicacies of the region may have had an impact on him. I told him my wife was along and he had a staff member radio down the hill to send her up.

We sat under a tarp hanging between two portable trailer-offices. This is where the crew took their breakfast. He called for tea and began the interview. I wasn’t sure where to start. He’s said all this before, he’s written articles and a book on the subject – much of it in German, however – and I didn’t want to ask him things that had already gotten into magazines had been distilled into a Wikipedia page complete with references and supporting links.

He knew Cedric Bodet, the only name I could drop, my old friend from Ankara who is also an archaeologist studying the Neolithic period and had done some work at this site. Though I sensed we had interrupted him, he quickly warms to the questions and runs with the answers.

“Tito forbade goats,” Schmidt told me, referring to the former dictator of Yugoslavia who outlawed the animals in regions he wanted protected. “Sheep will eat the grass, but goats eat roots.” Comparing the abundance of wildlife in the rock carvings – ducks, foxes, cranes, eagles, snakes, fish, rabbits, scorpions — and the desolate landscape stretching to the horizon is a sobering moment. Then he launched into what he had done here and was still doing.

Everything Mustafa had said started to sound like a grudge and a twist of misunderstanding. Why did the site look to be developing so slowly? The professor never had the intention of excavating it all. Perhaps future generations might do so, but he wanted to uncover the “gist” of it, let’s say, and analyze that carefully. Once you excavate something, you destroy it, he told me. There is no going back. A conspicuous mound of fill stood right in the center of Circle D, the highest and perhaps most impressive of the circles at the site. The two center t-shaped pillars stood on either side of it and its edges were clear like the last piece of cake in the center of the pan. So after nearly 20 years, indeed, why is that still not done?

Because he is waiting for technology to catch up, said one article, and he repeated the apology when I asked. In the past there was only one way to see what was down there: dig. Nowadays there are methods for scanning the earth without picking up a trowel. In fact, Schmidt knew the layout of this site years ago using such technology. There is no guesswork in where to dig. Many of these circles lie as many as 15 meters below the surface of this artificial hill and he knows their locations and general characteristics. No need to dig, in that regard. Two recent excavations to the west are being done only to confirm his belief that they are all generally the same in design. So far, that holds to be true.

So what of the last piece of fill-cake back in Circle D? A recent technological method called Optically Stimulated Luminescence dating. In the case of pottery or ceramics it can be used to determine when the piece was heated in a fire or kiln to more than 400 degrees Celsius. It can also look at a rock that has just been uncovered and tell us when that rock was last exposed to sunlight, thus helping to determine the date of a burial for example, or in this case, the date when the site was purposefully filled in with rubble. This works with crystal varieties of stone, granite, for example. Unfortunately, there is no technique that works with the limestone of this particular site. Not yet, anyway. If Schmidt pulls those stones, the chance to use a future method to get an accurate date of when this site had been filled in would be lost. Mustafa’s hardworking eagerness to dig it all bare would be his undoing if he were studying the site.

As for the “nearly 20 years” he’s been working here, take that with a grain of salt as well. The summers here bring temperatures up into the 50s Celsius; not especially favorable to human labors. And winters turn bone chilling and the rains don’t make for good digging. Schmidt and his team, then, are only digging in spring and fall.

Even before the instantaneous nature of internet life, before the speedy images of the MTV generation, one-hour documentaries on public television could give viewers the false impression that the teams come running in like Indiana Jones, pull out their trowels and toothbrushes, roll up their sleeves, and voila! the city of Ephesus rises from dirt. (In fact, I first saw “all” of Ephesus back in 1998. Over a decade later I visited again and a hillside of mosaic-floored villas had been excavated and opened to the public, as had some gladiator tombs.) The point is that this all takes time and great care if one wants to do it right. And again, one is destroying something with every stroke of a brush or swipe of a trowel.

“In one day we find millions of artifacts.” That’s a figure to raise some eyebrows, but artifacts are not just tools or relics or potsherds; artifacts are anything human made. So if flint knapping had been going on here, the tool or blade created in the process was an artifact – as were the several hundred flakes left behind in the dust.

I ask him, “What’s the big hole in the wall in two of the circles?” He chuckles to himself and shakes his head. “We don’t know, of course.” There are hypotheses. Andrew Collins, who authored three books on his takes on some archaeological mysteries, believes it has astronomical significance, that it is related to the location of Deneb, the brightest star in the constellation Cygnus. Schmidt doesn’t find that reasonable and brings it up only to wave it away.

Grooves and indentations along the tops of the pillars are also fodder for theorizing. It may have meant there was a roof on this. But there is no way of knowing and no evidence to further support any of the ideas. One could go through the site and place signs at every turn with just a giant question mark on them.

Our interview winds down as we finish a second round of tea, and we take photos of Schmidt with his recent excavations in the background. He gives me a signed copy of his book and we leave him to his work.

UNESCO recognition may be only a couple of years away. Things will change then. The protection of the site will change, the admission of visitors will change. Buses will no longer approach the site but park down the hillside so that a shuttle can ferry the guests back and forth. Numbers will need to be controlled as the pathway around the small site won’t accommodate a mob and by Schmidt’s estimation there are already over 1000 visitors per day during the weekends in high season. Just during my own two-hour visit at least a dozen full buses rumbled in and out of the lot.

At this point, they were laying down railroad ties as a suspended walkway. Yet there were no restrooms even. Just a ticket seller, who may or may not be actually selling tickets to all of the tourists, but collecting the money anyway.

And that brings us back to Mustafa. “Who are you? You don’t know to wipe your ass!” Mustafa had said in a rhetorical conversation with an absent site worker when we were back at the hotel. Turns out he may have said it in person this time. We can’t find him when we come back down from our meeting with Schmidt. We find him off behind the buses, uncharacteristically not chatting with someone, sitting alone in the car.

And that brings us back to Mustafa. “Who are you? You don’t know to wipe your ass!” Mustafa had said in a rhetorical conversation with an absent site worker when we were back at the hotel. Turns out he may have said it in person this time. We can’t find him when we come back down from our meeting with Schmidt. We find him off behind the buses, uncharacteristically not chatting with someone, sitting alone in the car.

He is steamed because now that ticket taking has become the rule, he is being pushed aside by some at the site. Other guides come in without paying. He is expected to pay for a ticket because he doesn’t have a guide’s license. He may lose that argument with an authority and his confrontation at the site may have been the result. For 5 TL he could just as well roll it into his tour price without any guests really caring about such a trifling amount. But he is a highly principled man – he fears God, he tells me periodically to explain his business ethics, picking at the thick hairs on his arms and pointing up — and this ticket collection is a matter of principle for him. But in fact it may be more a matter of official policy, especially once UNESCO accepts the park into its catalog of World Heritage Sites.

But in this crowd he could not find a patient ear. One of the site guards came at him with his fists flailing. “But why?” I asked. “That you ask him! I don’t know!” “Well, that’s awfully strange,” I said, with perhaps a hint of irony. “What would make him so angry?” Mustafa just snorted, but I could see how agitated he was, the adrenaline still in his veins, the sting of humiliation in his cheeks. He changed the subject: “Did you ask him? What he do for 20 years?”

“Ah, you know? I forgot actually.”

Mustafa grunted and nodded, as if I had proven his point. We sat in silence for the drive back into town: He with his indignation, and I with my daydreams of worshipping hunters climbing the hillside to humanity’s first monument to the powers of an inscrutable universe.

_______________________________________

For my article about Göbekli Tepe, check the Mad Traveler site. There is also a Göbekli Tepe photo gallery there.

Enjoy more posts from Southeastern Turkey! Click here for the Gaziantep trip.

For more articles and photo galleries about Turkey and Turkish culture, see The Mad Traveler home site.

ORDER YOUR COPY TODAY!

ORDER YOUR COPY TODAY! ORDER YOUR COPY TODAY!

ORDER YOUR COPY TODAY!

Pingback: Urfa: Mustafa and a Neolithic Rant