The Kindness of Strangers: Syria

Much is being said about the Syrian refugees and whether the United States (and other countries) should be taking them in. Mostly it is speculation and assumption, and much of the negative reaction is simply based on fear, prejudice, or ignorance. The United States has taken in loads of refugees over the years and it seems the biggest problem is the usual reaction of the hateful “I was here first” crowd (who think they were always here) and those who consistently fear “the other.”

The latest waves of immigrants always get run through the gauntlet of derision. Just go back and look at the ethnic jokes over the years. Not too many Irish, Italian or Polack jokes anymore, though there used to be volumes of them. Trust me on the Polish ones; I heard aplenty as a kid and my Polish bloodline landed in the US in the 19th century. Today the jokes are aimed mostly at Mexicans, as well as Muslims (the latest religion to stand before the punch line). So while I am not surprised by the sputtering cries of paranoia and prejudice, I do hope they don’t affect our ability to help fellow human beings caught between Daesh/Assad on one side and a European population that doesn’t remember how they ran like hell (or wanted to) during World War II and the Americans who forget where their forefathers came from on the other.

While I do not propose that anecdotal “evidence” is enough to go by, I do feel compelled to write a bit about my experiences in Syria as a backpacker. This was back in 1998 and I was living and teaching in Turkey. Syria was reachable by bus, and thus a great destination for Eid al-Adha – Kurban Bayramı in Turkish – the religious holiday that honors the willingness of Abraham/Ibrahim to sacrifice his son (Isaac/Yitzhak) in obedience to Allah/Yaweh/God. Sound familiar at all? For me it meant a school holiday – “spring break” in Syria.

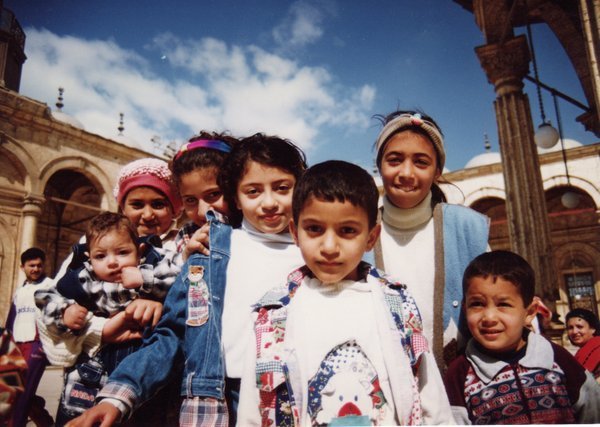

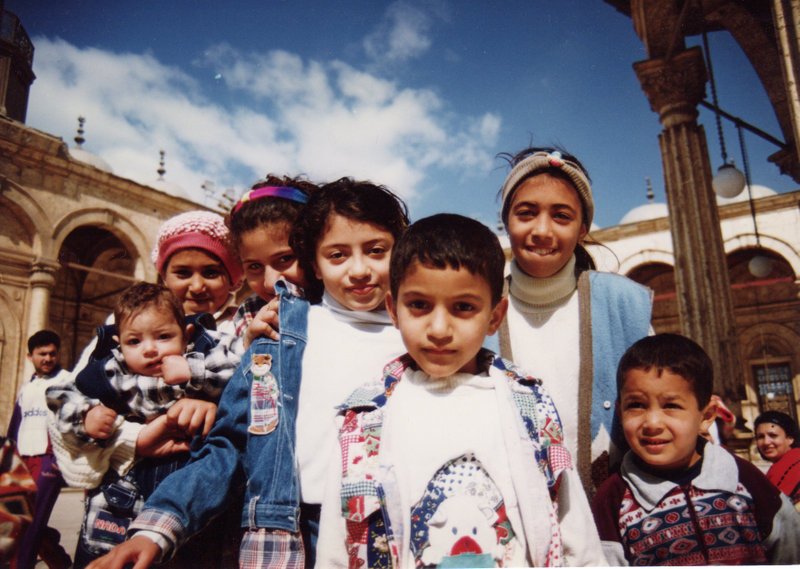

See the photo gallery: Children of Syria

My Ankara friends, Cedric and Canan – French and Turkish archaeology students, respectively – traveled with me by bus to the border of Syria. At the crossing we fell into conversation with a Syrian business woman, returning to Aleppo after a business trip in Turkey. At the border she donned a loose head scarf, which she hadn’t been wearing to this point. She shared a taxi with us from the bus station.

No matter where I went, I was met with friendliness, which became slightly more enthusiastic when anyone found out I was American. (And no, I never claimed to be Canadian or hid my nationality.) Most of the Syrians I met, of course, had never met an American. Some of them were Syrian middle class, others were rather poor, especially as we ventured away from the cities.

In Aleppo, I fell behind my friends as we wandered through the dark maze-like streets that night. I left my friends without notice, as I followed a strong fruity smell to a shop door. I poked my head inside and was invited into the back of the shop to share a round of shisha smoking with a group of men. They made no attempts to sell me anything; they just chatted with me a bit and savored the fruit-scented smoke. I had no concern about searching around a bit for my friends afterward.

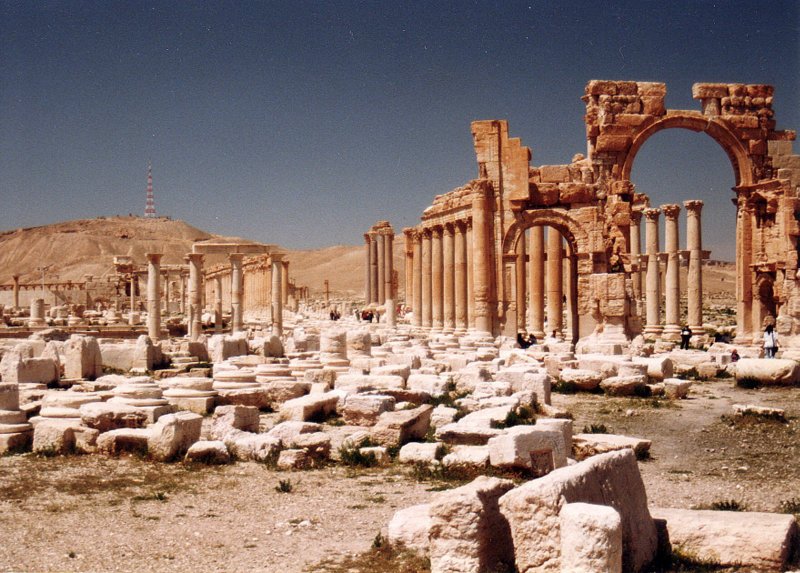

Crossing the desert one night in a shuttle van to the town and ruins of Palmyra (recently destroyed by Daesha), we met a local who insisted we come to his parents’ home for tea… at midnight. They turned on CNN to make us feel more comfortable. (Not the first time a foreigner figured an American needed to have a TV on to feel at home. Sigh.) We wandered at night amid the unguarded ruins, but the only thing that made us nervous was the nearby barking of a dog in the dark.

I am under no illusion that Syria doesn’t also have its creeps and crazies. Riding south to Damascus on a bus, the bus porter invited us to stay with his family in Busra. We politely declined but agreed to meet him for coffee in the coming days. Another passenger, Ferid, offered his home. After an hour of conversation, his friend Mohammad joined from the front of the bus and insisted he help us find a place in the city center. Now this character Mohammad made me cautious. When I had first sat down on the bus, he had stood before me and made a display of controlled impatience as he informed me that it was his seat. It didn’t matter to me and I moved, though I had been the first one on the bus and there were no seat reservations. The whole thing had seemed unSyrian; if I had sat in the driver’s seat, the driver would have leaned over me to steer rather than ask me to move.

Mohammad seemed a little manic and my travel sixth-sense put up the red flag. At the bus station in Damascus, the five of us shared a taxi into the city, but Mohammad only got more agitated as we drove from place to place as he looked for an available room. Night had fallen and after several stops, we were circling a block for the third time. Mohammad hopped out and ran into another building, we apologized profusely to Ferid who appeared mortified by the whole situation, and when Mohammad returned we were all standing on the walk with our bags. He got insistent and a little angry (red flags flying 100%) and we backed off with our bags. Before Mr. Insistent could insist more, a stranger intervened, and talked Mohammad into the taxi, sending them both on their way.

Our new advocate turned out to be Ahmed, an off-duty police officer. He made sure we were OK, then hopped in his pickup truck and left. We walked to the corner and tried to figure out where the hell we were on the map. (There was not an app for that at the time.) Then coming back around the block came that pickup truck. Ahmed saw we were lost, so he stopped again. Moments later Cedric hopped into the cab and Canan and I collapsed across our bags in the open bed. The adrenaline still fizzled in my veins and I was in love with the world, suspended in one of those timeless moments where you feel yourself at the center of life. A strange land, a new city, a place from the Bible passed before me in the wind. The streets of Damascus hummed beneath us and the streetlights glittered in our eyes. Minarets glowed green in neon, hotels, old and majestic, lined the avenues, and kebap stands and juice stands were awash in fluorescence. We gulped the chilling but invigorating air that rushed over us, tousled our hair, and rippled our clothes. Canan let out an enthusiastic cry as we passed through a tunnel. That night ride through Damascus – the stars not quite blotted out by city lights, the warmth of a stranger’s kindness still lingering in my chest – was one of the most memorable in my life. Ahmed left us after helping us check in at a budget hotel downtown.

We visited the old city the next day, seeing both churches and mosques, hearing Aramaic, Jesus’ language, being used at a mass, witnessing an Easter parade while hearing the call to prayer, visiting the tomb of Saladin, and the alleged resting place of the head of John the Baptist (a revered Muslim prophet), located inside Umayyad Mosque, the place where it is believed Jesus/Isa (another revered Muslim prophet) will return at the End of Days. That evening, we came upon a Santa Claus icon in a shop window. The shopkeeper invited us to sit on his stoop and share tea while we listened to an American 80s cassette playing Lionel Richie.

That night I fell seriously ill (long story short: leftover giardiasis/amoebic dysentery from Ramadan break in Egypt, not completely treated and relapsing with a violent vengeance). I was up all night nearly passing out on each trip down the hall to the restroom. The next day as a zombie, I decided I could no longer go on and when we arrived by bus to the desert town of Ma’loula, I put up the white flag. We stepped off the bus in front of a convent. Canan and Cedric inquired for me within, and the nuns offered me a bed for the night, brought me water, and watched over me, while I insisted my friends travel ahead a bit while I recuperated. A Lebanese pilgrim ended up also sharing the room, and – bless his heart – kept waking me up for friendly conversation.

a cellphone photo from a friend in Homs

The nuns tried to feed me breakfast — I could only swallow some stale bread before nausea insisted I stop – and guided me back to the bus, instructing the driver where I was going. The bus driver dropped me off along the desert highway to await the next northbound bus to Homs (yes, the Homs that was Syria’s 3rd largest city and is now one of its largest and most tragic rubble piles). The bus passed me by, but a van pulled over and I hitched for the two-hour drive. As I looked for a place to sleep a few hours before meeting up again with my friends at our agreed-upon meeting spot, the hotelier who took me in short-term for a few bucks paused to ask me if I was traveling with a Frenchman and a Turkish woman. Um… yes. Complete weakness from dehydration and the careful attention nausea demanded kept my alarm at his knowledge to a mere passing curiosity level, and I stumbled off to collapse on top of a bed, nearly forgetting to take my backpack off. (I never figured out how he knew who I was traveling with, but I think the nuns had called around town ahead of my arrival to check up on me.)

Still too ill to travel, I had my friends put me on the next shuttle north where I’d wait for them in Turkey for the bus ride home. An animated guy up front with the driver left me grumbling about obnoxious people, but when we pulled into the station, he was the first one to see I was uncertain where to go next. He took me by the arm, and walked me all the way to the bus station. A humbling moment after all the negativity I had silently heaped on him based on what I could only guess from appearances.

I crossed the border that night, on a double-decker bus full of big blue plastic barrels of diesel fuel. I was the only passenger, and the three operating the bus, one with a Russian passport, left me to pass out in my seat, waking me only for the border crossing, where smiles and bribes were exchanged. They dropped me off at the bus station – clearly they had another stop to make – with a cheery farewell. I wobbled back to the hotel where we had stayed a week earlier, checked in, and dropped like I’d reached the finish line. Then someone knocked on the door. At 1 am??? I got up, incautiously opened the door wide, and a stranger stood there with postcards. What the hell?? About to reply in Turkish that I didn’t want any, I saw they were all with Syrian photos, and across the backs were chicken scratches. My chicken scratches. I had dropped them somewhere between the bus station and this bed.

This is the world you experience, 99% of the time, when you travel through all those “dangerous” places. Yes, dangers exist and I wouldn’t dare go to Syria today, unfortunately, because it truly is an all encompassing war, not an isolated political conflict (such as the red-shirt protest, riots and violent crackdown in Thailand in 2010, which were easily avoided while we lived in Bangkok.) Am I afraid of Syrian refugees? Not on your life. I know there are logistical and real-world challenges and concerns about filtering a large population of displaced people into a new country and culture, but I don’t speak to that here. America has a long history of experience with this situation. (I grew up with Vietnamese new arrivals in a small town in Wisconsin in the 1970s. We share a hometown now.) The Syrians are some of the most hospitable people on earth and it is a deep part of their culture. Judging from the volume of hatred, fear, and vulgarity from many Americans during Syria’s time of need, I don’t think all of us can say the same.

_________________________________________________________

Kevin Revolinski is the author of The Yogurt Man Cometh: Tales of an American Teacher in Turkey, and is at work on a similar memoir of his travels through Egypt and Syria. To receive an alert when his new book is available, send an email with “Syria Book” in the subject line to revtravel [at] yahoo [dot] com. Your address will only be used for an eventual book notification.

ORDER YOUR COPY TODAY!

ORDER YOUR COPY TODAY! ORDER YOUR COPY TODAY!

ORDER YOUR COPY TODAY!

Beautifully written, thank you for sharing your experiences wow what a trip. It is truly a heart wrenching situation. I completely agree with your point of view.